English

Έτσι είναι (This is how things are) | Απόψε (Tonight) | Αντίδωρο (In return)

Timber Journal / Translated by: Pavlos Stavropoulos

This is how things are

In the sweaty room of some hotel an old man is shoving me into the bedspread. I struggle to breathe underneath his old wrinkled skin while he—wheezing and serious—pushes my body deep into the mattress. He crams his hands into my ribs, one after another, and his tongue—wet and icy—probes for life inside my mouth. His bristles, rugged and thorny, drill holes into my cheeks. Whenever I try to cry out my mother, thin and skeletal, appears. With her cold right hand, the one she crosses herself with, she covers my eyes tenderly and whispers: “This is how things are.” Her wrinkles gather her tears and I can think—with rage, exhaustion, and an inconsolable, dreary nostalgia—of you.

Tonight

Large and shiny like a kitchen knife, the eight o’clock train sliced the earth beneath us. I held your hand indifferently—just for the kids’ sake—and we climbed up the bridge, trying to catch up with the dust from the vanishing train’s last breath. I’m afraid that tonight—after days and many years—we will make love. I will undress you like a baby, and right there on the couch, with the tv’s blue light reflecting on your breasts and the children’s photos on the buffet, I will enter you violently, as if I am bursting. The cloth will rub on our backs and we will bleed a little and maybe upon finishing you will cry: for the children who have left, for your skin that has spoiled, for your white hair, and for me who, I’m afraid, will lie and tell you I still love you.

In return

Red hue on top of the boulders, the sun was close to setting behind the goats. Their bodies, tightly bound, cradled the iron bars, dripping watery blood upon the soil as if it were diluted. Their torrid scent would sneak into my nostrils and clench my innards. I scratched and licked the moistened stones; every now and then a muffled scream would seethe from beneath my teeth, a growl so terrible and enraged. “Quiet!” the man yelled all of a sudden. Then calmly, tenderly, almost laughing, he would bring me close to him, buying off my silence with a caress.

Two Stories by Ursula Foskolou

Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation (University of Iowa), Translated by: Pavlos Stavropoulos

Outside

The cold pierces my bones. I stay outside the whole night and watch all of you: the noisy, excitable mass, moving gracelessly to the rhythm of the music. You are buried somewhere in there, among them. And there are times when I cannot make out your face. Someone stands in front of you, sips his drink, hugs you and sweetly wishes you “happy birthday.” You put your arms around his neck, kiss him and continue to dance. I want to burst in with rage, to clear a way through the crowd, to shove everyone violently aside and drag you outside. To hit you for forgetting me and then force you into the car, to take you back home. I clench my teeth despite all this and control myself. Today is your birthday and a father, one who left early, can only watch from outside.

Upside down

In the middle of the noisy square, the man brandished the plastic wands, creating transparent and iridescent bubbles, which the wind would lure towards the heads of the passersby. One of the bubbles came and hovered in front of me. I glanced inside it and saw summer: sultry, sticky and wet, full of excitement, but inverted. At the top, I saw the azure chlorine of the swimming pool, red geraniums, fields with warm, freshly overturned soil, orange trees that dripped giant fragrant spheres upon the clouds. I saw the paper tablecloth barely holding on and the salad spoon that slowly poured bitter green olive oil onto the sky. I saw you afterwards, hanging hard onto the chair, your black hair flowing like water, and your white strands sinking again, like bulbs, inside the skull. I saw—I think—for a moment, your body naked, dark in the front and luminous in the back, diving towards the sky, upside down, approaching me. Quickly, I took money out of my pocket and bought the plastic wand.

One day I will create a large bubble. I will pierce it gently then will sit inside it, on a chair beside yours. I will brush your hair aside and will see you—one more time—even if upside down.

"The chickens" by Ursula Foskolou

Asymptote Journal / Translated by: Pavlos Stavropoulos

The chickens

I put the key in the door and I saw them: they were all standing upright and mute by the side of the bed. The relatives, a long coiled queue, were offering their hands and with straight rigid backs they were bowing like chickens. Centered on a hard pillow, my grandmother’s head was cold and in places translucent, like ice that had started to melt. I cleared a path violently and found myself there. The bed smelled from up close: violets, roses, and that earthy smell of old water that you have forgotten in the fridge for months. I lowered myself next to her ear and—speaking—I started to warm her with my breath. Small initially and then wider, the hole was dripping incessantly, soaking the pillow. By midday, she was gone. My grandmother, all of her, flowed into a small basin, and the chickens at her side made a queue to quench their thirst.

Italian

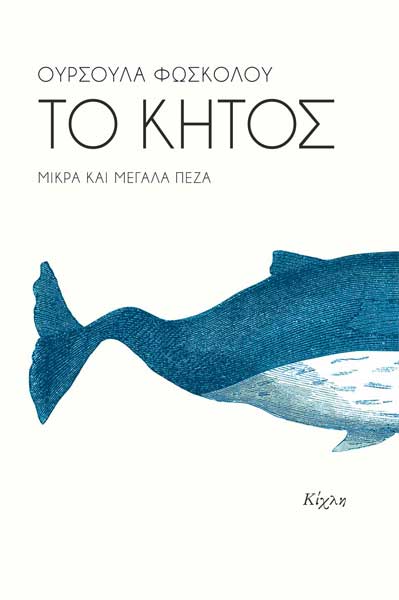

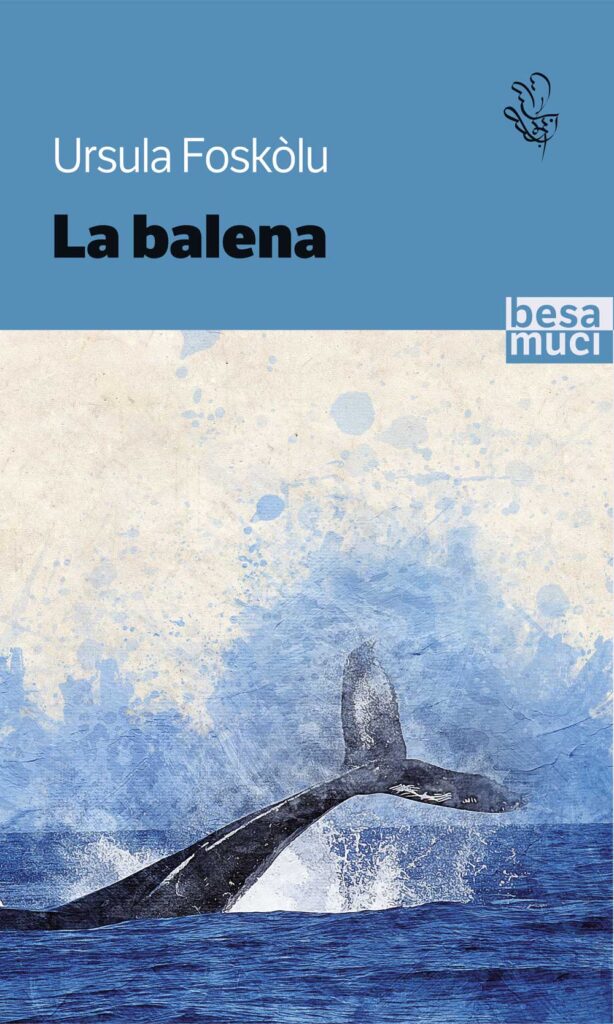

La Balena

Besa Muci, Traduzione: Francesca Zaccone

La Balena di Ursula Foskòlou è una raccolta di racconti bonsai o microfiction che illuminano, come riflettori in miniatura, brevi storie di vita interiore, di desiderio bruciante, ma anche di paralisi e nostalgia. Storie di formazione e di duro ritorno al mondo crudele dell’infanzia, dove regna la solitudine. Nella favolosa pancia della Balena tutto può succedere: la florida fantasia e l’audacia espressiva di Ursula Foskòlu ignorano le regole della logica e trasformano il vissuto individuale in un’esperienza strana ed estraniante, resa con immagini e metafore che rievocano lo sguardo stupito dei bambini. Gli stati d’animo si espandono assumendo dimensioni simboliche, e i protagonisti acquistano una profondità archetipica che li proietta ben oltre i limiti della quotidianità.

Traduzione a cura di Francesca Zaccone.

Finnish

Valas

Translated by: Riikka P. Pulkkinen

Siitä on jo vuosia, kun minut nielaisi kala. Istuin autiolla hiekkarannalla syyskuisen hämärässä illassa, jonka lämpõ tuntui keväiseltä. Seitsemän laiva kulki ohitseni – valaistuna – ja tiesin sinun olevan sen sisällä, lasten juoksentelevan, äitisi istuvan vieressä kulmat kurtussa ja hänen pitelevän sinua sylissään. Huusin raivoissani: “Tulkoon valas nostattamaan aallon, rikkomaan evillään laivan pohjan. Jotta sinä katoaisit”. Ja se tuli: hitaana, uhkaavana, valtavana se pysähtyi rantaan leuat ammollaan. Vesi valui sen hampaista kuin läpinäkyvä verho. Riisuuduin ja astelin sisään sen pitkää, kosteaa kieltä pitkin, istuuduin sen suuhun. Olemme seuranneet sinuajo vuosien ajan: valas haluaa nielaista sinut ja minä – iäti – pidättelen sitä.

Antologia Kasvotusten. Nykykreikkalaisia novelleja

Turkish